Mathematica Programming » Assorted Tricks

Object Oriented Programming

Mathematica is a functional programming language, which, for the purposes of the current discussion, basically means that everything has a purely symbolic representation. Often we talk about things not have state which is to say, they don’t have attributes.

This makes Mathematica code very deterministic and results easy to store, but sometimes using something with state can be useful. We call these things with state objects and so programming with things with state is called object oriented programming (OOP).

This is a very powerful programming paradigm and, in fact, the (probably) most popular languages are all object-oriented. Java, Python, and C++ all make extensive use of objects in the form of classes, instances, templates, interfaces, etc.

We can work OOP into our standard Mathematica programming, although it can be a tough job to do.

Association Interfaces

The simplest and probably most widely used form of OOP in Mathematica isn’t true OOP. We still have symbolic stateless objects, but, critically, it looks like they have state.

The basic idea is that our object will be defined by an association, then we’ll give it a head so that it can be easily distinguished for pattern matching and operator overloading.

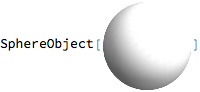

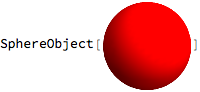

We’ll do this for an object called SphereObject

First, we need a nice way to make a new one of these:

SphereObject[attrs:(_Rule|_RuleDelayed...)]:=

SphereObject[

Merge[{<|"Radius"1,"Color"White,"Position"{0,0,0}|>,<|attrs|>},First]

];

Then we’ll need a way to set and get attributes. We’ll do this via SubValues . To be extra fancy, we’ll also write it so that if our returned argument is a Function , that gets called with the object and passed arguments:

SphereObject[attrs_Association][k_,args___]:=

With[{r=attrs[k]},

If[MatchQ[r,_Function],

r[SphereObject[attrs],args],

r

]

];

Then do something for setting / removing attributes with UpValues :

SphereObject/:HoldPattern[

Set[SphereObject[attrs_Association][k_],v_]

]:=SphereObject[Append[attrs,k->v]];

SphereObject/:HoldPattern[

SetDelayed[SphereObject[attrs_Association][k_],v_]

]:=SphereObject[Append[attrs,k:>v]];

SphereObject/:HoldPattern[

Unset[SphereObject[attrs_Association][k_]]

]:=SphereObject[KeyDrop[attrs,k]];

Last, assign some Format form to the object:

Format[SphereObject[attrs_]]:=

With[{

r=Replace[attrs["Radius"],_Missing1],

c=Replace[attrs["Color"],_MissingWhite],

p=Replace[attrs["Position"],_Missing{0,0,0}]

},

Interpretation[

Deploy@

Style[

Row@{"SphereObject","[",

Graphics3D[{c,Sphere[p,r]},

Lighting"Neutral",

BoxedFalse,

Method{"ShrinkWrap" -> True}],

"]"},ShowStringCharactersFalse],

SphereObject[attrs]

]

];

SphereObject[]

SphereObject["Color"Red]

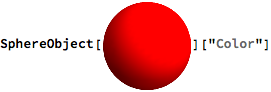

Note that we can pull values from these objects:

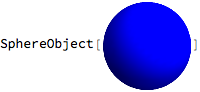

And we can set them:

And unset them

Each of these is really just an Association at heart, though. There is no state. These aren’t real objects.

Managed Types

To get state, we have to track state. And to track state, we need some form of state manager. So we’ll take a hint from our front end objects and write our own and then define objects relative to that.

This time we’ll make a StringObject

We’ll start with a manager. Just an association that will track things by ever-increasing ID.

$StringObjectCounter=1;

$StringObjectManager=<||>;

Then a constructor, once more, but this time the constructor adds an entry to the manager table:

StringObject[s:_String:"",styleSpecs:((_Rule|_RuleDelayed)...)]:=(

$StringObjectManager[$StringObjectCounter]=

<|"String"s,styleSpecs|>;

StringObject[$StringObjectCounter++]

);

We’ll use the same attribute get / set structure as before, except this time routed through an ID:

StringObject[ID_][k_,args___]:=

With[{attrs=$StringObjectManager[ID]},

If[!MatchQ[attrs,_Missing],

With[{r=attrs[k]},

If[MatchQ[r,_Function],

r[StringObject[ID],args],

r

]

],

Missing["NoObject",StringObject[ID]]

]

];

StringObject/:HoldPattern[

Set[StringObject[ID_][k_],v_]

]:=

With[{attrs=$StringObjectManager[ID]},

If[!MatchQ[attrs,_Missing],

$StringObjectManager[ID][k]=v,

Missing["NoObject",StringObject[ID]]

]

];

StringObject/:HoldPattern[

SetDelayed[StringObject[ID_][k_],v_]

]:=

With[{attrs=$StringObjectManager[ID]},

If[!MatchQ[attrs,_Missing],

$StringObjectManager[ID][k]:=v,

Missing["NoObject",StringObject[ID]]

]

];

StringObject/:HoldPattern[

Unset[StringObject[ID_][k_]]

]:=

With[{attrs=$StringObjectManager[ID]},

If[!MatchQ[attrs,_Missing],

KeyDropFrom[$StringObjectManager[ID],k];,

Missing["NoObject",StringObject[ID]]

]

];

And build a similar format although this time we’ll want a special format if the object doesn’t exist:

Format[StringObject[ID_]]:=

With[{attrs=$StringObjectManager[ID]},

If[!MatchQ[attrs,_Missing],

With[{

s=Replace[attrs["String"],_Missing""],

o=Sequence@@Normal@KeyDrop[attrs,"String"]

},

Interpretation[

Deploy@

Style[

Row@{"StringObject","[",

Style[s,

"Output",

o,

BackgroundNone,

ShowStringCharactersFalse

],

"]"},ShowStringCharactersFalse],

StringObject[ID]

]

],

Unevaluated[StringObject[ID]]

]

];

Then test this:

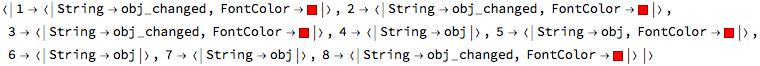

S=StringObject["obj"]

StringObject[8]

But now it’s got state:

With[{S=S},S[FontColor]=Red]

S

StringObject[8]

With[{S=S},S["String"]="obj_changed"]

"obj_changed"

S

StringObject[8]

All of these are the same object, though:

InputForm /@ {StringObject[8], StringObject[8], StringObject[8]}

{StringObject[8],StringObject[8],StringObject[8]}

This is now an object with attributes and state, which means that within a session it is more powerful, but we can’t figure out what it looks like (attribute wise) from the symbolic form alone. Here is where our manager comes into play:

$StringObjectManager

This is all the string data for all of the objects we made this session. By caching this, we can retrieve the state of our system trivially.

Types as Symbol Interfaces

There is one last (common) way to do object orientation. Rather than using a centralized manager, which if it gets corrupted or deleted can destroy the state of our system, we can use a symbol interface.

We do this by creating a symbol where before we created an ID. In fact, this really blurs the line between a managed type and an association interface.

This time we’ll outline a timer object.

Instead of using ID, we’ll assign an association to a symbol. This means we need to hold our symbol, though, to prevent it from evaluating. We will also want to keep track of which symbols we have used. We’ll do this via an association because lookup in associations is much faster than in lists:

$TimerObjectCache=<||>;

TimerObject[]:=

With[{obj=Unique@"timer"},

$TimerObjectCache[TimerObject[obj]]=None;

obj=<|

"CheckPoint"->Now,

"EndPoint"->None,

"Toggle":>(

With[{o=#},

o["EndPoint"]=

Replace[o["EndPoint"],{

None->Now,

_->None

}]

]&)

|>;

TimerObject[obj]

];

TimerObject~SetAttributes~HoldFirst;

TimerObject[sym_][attr_,args___]:=

With[{r=sym[attr]},

If[MatchQ[r,_Function],

r[TimerObject[sym],args],

r

]

];

TimerObject/:

HoldPattern[HoldPattern[Set[TimerObject[sym_][attr_],v_]]]:=(sym[attr]=v);

TimerObject/:

HoldPattern[SetDelayed[TimerObject[sym_][attr_],v_]]:=(sym[attr]:=v);

TimerObject/:

HoldPattern[Unset[TimerObject[sym_],attr_]]:=(sym[attr]=.);

Format[TimerObject[sym_]]:=

With[{

start=sym["CheckPoint"],

end=Replace[sym["EndPoint"],NoneNow]},

Interpretation[

Deploy@Style[

Row@{"TimerObject","[",

Framed[

NumberForm[end-start,3],

RoundingRadius5,

BackgroundLighter[Blend@{LightBlue,Gray},.8],

FrameStyleGrayLevel[.6]

],"]"},

ShowStringCharactersFalse

],

TimerObject[sym]

]

];

t=TimerObject[]

Pause[1];

t

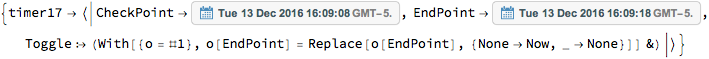

TimerObject[timer17]

TimerObject[timer17]

Note that these are obviously the same object

And we can access state:

With[{t=t},t["Toggle"]]

t

Pause[1];

t

TimerObject[timer17]

TimerObject[timer17]

t["EndPoint"]

This is a more powerful method that using a manager and it’s harder to accidentally delete one’s data. Unfortunately, saving state is somewhat harder, though. This is why we tracked our objects built.

With[{objs=$TimerObjectCache//Keys},

#ReleaseHold@#&/@(HoldForm@@@objs)

]

We now have to save all of these definitions but it is doable.

Summary

The order in which we’ve seen these object management structures more or less corresponds to their order of flexibility and also complexity.

Using a state-less object-like wrapper (an interface to an association, basically) is easier but less flexible than using objects that reference an object manager, which are in turn harder to use and less powerful than objects that track their own state.

Moreover, this is just a primer on making objects. Languages such as Java, Python, and C++ have a much richer object interface, including classes, instances, interfaces, templates, etc. To implement all of that is beyond the scope of this tutorial, but the tools we have here are actually sufficient to do so (at least for classes and instances).

In general, though, it is best to use the object you need for the project you need, until you’re comfortable enough to build a more general architecture.