Mathematica Programming » Code Structure

Functions

Functions as Patterns

The reason for that long discussion of patterns is the following: Mathematica functions (except pure functions) are just patterns. Consider the following:

f[x_]:=x*10

All I've done here is tell the system that whenever it sees the pattern f[Blank[]] execute the right hand code, but with x replaced with the value of that Blank[] .

Seeing as that's all we're doing, though, we can also leverage the power of patterns to restrict our definition:

g[i_Integer]:=RandomInteger[i];

g[s_String]:=RandomChoice@Characters@s;

g[{v_,___}]:=g[v];

Now we have a function g that can vary depending on its arguments.

g/@{10,"my word!",{g,c,d}}

{2,"w",g[g]}

One thing worth noting is that if a multi-element pattern is matched, the values are substituted as the arguments of the enclosing head, but if the values themselves are returned they are wrapped in Sequence for consistency. For instance:

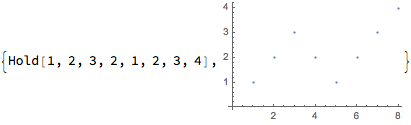

g[s___]:={Hold[s], ListPlot[{s}]};

g[1,2,3,2,1,2,3,4]

g2[s___]:=s;

g2[1,2,3,2,1]

Sequence[1,2,3,2,1]

Named Patterns, Optional and Disappearing Arguments

A Pattern can be declared without any underscores by following it with a colon. This is useful in function declarations when you want to get the value of a complicated pattern element, for instance:

h[a:(_Integer|_String|π)]:=Head@a;

h[_]:=2

h/@{1,"1",π,h,{"H","i","M","o","m","!"}}

{Integer,String,Symbol,2,2}

Pattern has a cousin, however, called Optional who also uses a colon, but who can only be called on top of an existing Pattern :

a:_:Automatic//FullForm

Optional[Pattern[a,Blank[]],Automatic]

MatchQ works with Optional by just matching the pattern beneath

MatchQ[1,a:_Integer|_String:Automatic]

True

What makes Optional special is its behavior in functions. It has a special simplest form which you may have seen already in a function declaration:

a_:Automatic//FullForm

Optional[Pattern[a,Blank[]],Automatic]

And now observe what this can do for us:

optionsFunction[arg_:Automatic]:=arg;

optionsFunction[1]

optionsFunction[]

1

Automatic

Notice how we didn't need to supply a value. How Optional works is that if the Pattern doesn't match, the default value gets substituted instead. What makes this special is the following sort of thing:

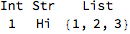

opF[intArg:_Integer:1,strArg:_String:"Hi",listArg:_List:{1,2,3}]:=Grid@{

{"Int","Str","List"},

{intArg,strArg,listArg}

};

opF[]

opF[{1}]

opF["a",{1}]

opF[10, {1}]

Notice how we didn't even need to specify all of our arguments to change our list argument. This is because a List wouldn't match _Integer or _String so these took on their default values, but the list argument took the value supplied.

This sort of trick only works when the argument patterns are disjoint enough, but often they are. At base, it means that complicated functions can be declared more concisely. Moreover, it is a crucial thing to know when dealing with OptionsPattern

Attributes

I'm mentioning Attributes here only because I would be remiss not to. All Symbol s can have Attributes in Mathematica and as functions are Symbol s, they can too. There is a list of permitted Attributes and trying to set an undefined attribute will cause an error to be raised:

SetAttributes[a,hat];

Attributes@a

The point of Attributes is generally to change the evaluation behavior of a symbol. The most useful Attributes in my mind are HoldFirst , HoldAll , and Listable all of which change how a definitions on a Symbol are applied.

HoldFirst and HoldAll designate that some portion of their arguments (either the first or all of them) should not be evaluated before being substituted into the code of their function definition. For example:

atF~SetAttributes~HoldFirst;

atF[arg_]:=Hold[arg];

atF[N[π]]

Hold[N[π]]

If atF did not have this, N[π] would have evaluated first:

ClearAttributes[atF,HoldFirst];

atF[N[π]]

Hold[3.141592653589793`]

HoldAll has the same behavior, just every argument is held. (There is also a HoldRest attribute which should be self explanatory). There is however also an attribute HoldAllComplete which behaves like HoldAll except even UpValues are not applied (this is probably a meaningless statement, but there is a section dealing with UpValues soon)

Listable changes evaluation behavior by specifying that the function should be applied to the elements of any List in its arguments. This is made clear better by the documentation, but there is a useful case to know about, where this behavior is important.

StringJoin joins strings, obviously, but it also has the attribute Listable which means that rather that requiring

StringJoin["a","b","c","d"]

"abcd"

It can take:

StringJoin@{"a","b","c","d"}

"abcd"

But where this is really useful is in the alias form of StringJoin ( <> ). If it did not have Listable we'd have to do the following:

"a"<>"b"<>"c"<>"d"

"abcd"

But since it does we can drop some of those <> for a list:

""<>{"a","b","c","d"}

"abcd"

This behavior may seem unimportant now, but it can be incredibly useful when in the midst of a large project and needing to try out different things. Converting your entire list to <> joined pairs can be annoying, or maybe you already had some joins in there. In any case, it can save time and brain power which could be better used on actual programming.

Options, OptionsPattern, OptionValue, and FilterRules

Much like Attributes a Symbol can also store Options . These are a list of Rule s with default values which are used by functions via the OptionValue interface. There's a convenient Pattern called OptionsPattern which will match Rule and RuleDelayed sequences among other things. The Options interface is rich, so check out the documentation on it, but I'll provide some tips, tricks, and common uses cases

One thing to keep in mind is that since OptionsPattern matches a block of Rule and RuleDelayed , it can be useful to declare that all of the arguments before this block (or after it) are not Rule or RuleDelayed

Options[opEx]={"X"->0,Y->0,1->5,{1,2,3}->3};

opEx[notRuleArgs:Except[_Rule]...,ops:OptionsPattern[]]:={

{notRuleArgs},

{ops}

};

opEx[1,2,3]

opEx[1, 2, "X"->1000]

opEx[1, 2, "X"->1000,A->20]

{ {1,2,3},{}}

{ {1,2},{"X"->1000}}

{ {1,2},{"X"->1000,A->20}}

When using Options in a function one uses OptionValue to get the value, which will first check to see it's been overridden in an argument and if not go to the default value:

opEx[notRuleArgs : Except[_Rule] ..., ops : OptionsPattern[]]:=OptionValue@"X";

opEx[1,2,3]

opEx[1, 2, "X"->1000]

0

1000

If you call an OptionValue for which there is no default, you'll get an error:

opEx[notRuleArgs : Except[_Rule] ..., ops : OptionsPattern[]]:=OptionValue@Z;

opEx[1,2,3]

Z

Even if you provide an explicit override value, it will still grouse at you, although it will work:

opEx[1,2,"Z"->500]

500

Options are generally used to provide more flexibility and control than can easily be done via an argument list. Options can also be used as a function to see all of the default options for a symbol and for many of the built-in symbols you can see how many there are, so that users can tweak lots of things. For example, Plot has a whole host of options:

Options@Plot

{AlignmentPoint->Center,AspectRatio->1/GoldenRatio,Axes->True,AxesLabel->None,AxesOrigin->Automatic,AxesStyle->{},Background->None,BaselinePosition->Automatic,BaseStyle->{},ClippingStyle->None,ColorFunction->Automatic,ColorFunctionScaling->True,ColorOutput->Automatic,ContentSelectable->Automatic,CoordinatesToolOptions->Automatic,DisplayFunction:>$DisplayFunction,Epilog->{},Evaluated->Automatic,EvaluationMonitor->None,Exclusions->Automatic,ExclusionsStyle->None,Filling->None,FillingStyle->Automatic,FormatType:>TraditionalForm,Frame->False,FrameLabel->None,FrameStyle->{},FrameTicks->Automatic,FrameTicksStyle->{},GridLines->None,GridLinesStyle->{},ImageMargins->0.`,ImagePadding->All,ImageSize->Automatic,ImageSizeRaw->Automatic,LabelStyle->{},MaxRecursion->Automatic,Mesh->None,MeshFunctions->{#1&},MeshShading->None,MeshStyle->Automatic,Method->Automatic,PerformanceGoal:>$PerformanceGoal,PlotLabel->None,PlotLabels->None,PlotLegends->None,PlotPoints->Automatic,PlotRange->{Full,Automatic},PlotRangeClipping->True,PlotRangePadding->Automatic,PlotRegion->Automatic,PlotStyle->Automatic,PlotTheme:>$PlotTheme,PreserveImageOptions->Automatic,Prolog->{},RegionFunction->(True&),RotateLabel->True,ScalingFunctions->None,TargetUnits->Automatic,Ticks->Automatic,TicksStyle->{},WorkingPrecision->MachinePrecision}

This is also useful for chaining functions together and passing their options to each other. Before an example of that, it's worth talking about FilterRules . All it does is take a list of rules and either an explicit list of rules or rule names or a pattern to match and selects those rules whose left-hand side matches. For example:

FilterRules[Options@Plot,PlotStyle|EvaluationMonitor]

{EvaluationMonitor->None,PlotStyle->Automatic}

This can be used to make sure rules conform to the options of a given function:

FilterRules[{"Z"->10,"X"->100},Options@opEx]

{"X"->100}

Finally as OptionValue matches the last pattern it sees, one can pass all the defaults for a symbol plus some updates by putting your new rules first in a FilterRules :

ClearAll@opEx

Options[opEx] = {"X" -> 0, Y -> 0};

opEx[notRuleArgs : Except[_Rule] ..., ops : OptionsPattern[]] := OptionValue@"X";

FilterRules[Join[{"Z"->10,"X"->100}, Options@opEx], Options@opEx]

opEx@@FilterRules[Join[{"Z"->10,"X"->100},Options@opEx],Options@opEx]

{"X"->100,"X"->0,Y->0}

100

This trick is necessary when overriding options on an old function:

Options[newGraphics3D]=Join[{

Lighting->"Neutral",

Boxed->False,

ImageSize->Small

},

FilterRules[Options@Graphics3D,Except[Boxed|Lighting|ImageSize]]

];

newGraphics3D[graphicsStuff:Except[_Rule]...,ops:OptionsPattern[]]:=Graphics3D[{graphicsStuff},

FilterRules[Join[{ops},Options@newGraphics3D],

Options@Graphics3D]

]

newGraphics3D@Sphere[]